![]()

![]()

![]()

Use LEFT and RIGHT arrow keys to navigate between flashcards;

Use UP and DOWN arrow keys to flip the card;

H to show hint;

A reads text to speech;

70 Cards in this Set

- Front

- Back

|

INTRODUCTION |

An Agency relationship is: The fiduciary relation which results from the manifestation of consent by one person to another that the other person shall act in his behalf and is subject to his control; and consent by the other so to act |

|

|

The law governing agency in Sri Lanka is the law applicable in England. |

This is made clear by section 3 of the Civil Law Ordinance No. 5 of 1852 which states that, “in all questions or issues which have to be decided in Sri Lanka with respect to the law of principal and agent, the law to be administered shall be the same as would be administered in England in the like case.”

Accordingly, English cases on agency disputes will apply in Sri Lanka. There is no main statute law applicable to agency. The law of agency is therefore found mainly in common law principles decided by the courts. |

|

|

Fridman cited Valin J in Labreche v Harasymiw |

Agency is the relationship that exists between two persons [or parties] when one, called the agent, is considered in law to represent the other, called the principal, in such as way as to be able to affect the principal's legal position in respect of strangers to the relationship by the making of contracts or disposition of property |

|

|

Creation of Agency by express agreement |

the appointment of the agent is made in writing or verbally. In formal cases when written appointments are made, it is done by a power of attorney which is normally stamped and registered. Example : If a customer of a bank wishes to transact his banking business through an agent, the bank will require written evidence of the appointment of the agent and will normally ask to see the registered power of attorney appointing the agent. |

|

|

Creation of Agency by implied agreement |

There is no evidence that the agent has been appointed by any writing or verbally. But, there are facts and circumstances that can show that an agency has been created. In other words, agency is implied from the special circumstances of the case. Example : For several months, Piyal (the principal) has paid Prasad (the third party) for goods sold on credit by Prasad to Sunil (the agent) for Perera’s use and benefit. Piyal had never disputed Sunil’s authority to receive the goods given to him by Prasad. Therefore, by conduct there is an implied agreement that Sunil was acting as Piyal’s agent when buying goods on credit from Prasad. |

|

|

Creation of Agency by operation of law I. Agent of necessity |

An agent of necessity can be described as a person who, in circumstances of an emergency (for example, a person’s property being in danger of destruction) acquires by operation of law, a presumed authority to act as an agent. Here, some unforeseen events can create an agency and the agency relationship can arise even against the intentions and wishes of the parties concerned. The object of the law in these circumstances is to recognize the inability of the agent to communicate with the principal. In the context, commercial necessity imposes on the agent the duty to act in good faith in the interest of all the parties. The legal rules relating to agents of necessity seek to achieve common sense in day to day human life. Example : Piyal has a large coconut property on which Sunil is the caretaker. When Piiyal is abroad, there is a huge fire on the coconut property. Sunil becomes an agent of necessity for Piyal so as to save the property from being destroyed by fire. Piyal (the principal) will be liable for any expenses, Sunil (his agent of necessity) incurred to put out the fire and save the coconut property from destruction during Piyal’s absence from the country |

|

|

Lapraik v Burrows (1859) 15 |

when the ship arrived in the harbor, the captain found that the ship was unseaworthy and could not be put out to sea. So he decided to save further loss and sold the ship. The owners of the ship were held liable for the act o f the captain who was regarded as their agent of necessity. |

|

|

China-Pacific SA v Food Corp of India: |

§ Facts: Ship became stranded on reef and the managing agent entered into an agreement for salvage to get the wheat off the ship. Plaintiff transferred it to Manilla – sought cost for warehouse based on the idea that there was an agent of necessity § Held: No agent of necessity. It was not impossible to communicate with the cargo owners and get their express instructions for what they wanted to do Lord Ziplock's two-fold division of agency of necessity: 1. Where an agent enters into a contract with 3rd party on behalf of P, binding P and 3rd party; AND 2. Where a person acts for another and subsequently seeks reimbursement or a indemnity from him |

|

|

Springer v. Great Western Railway Company |

Great Western Railway Company as defendant agreed to carry plaintiff’s tomatoes from Channels Island to London, by ship to Weymouth and by train to London. The ship was stopped at Channels Island for three days due to bad weather. Eventually, when the ship arrived at Weymouth, defendant’s employees were on strike, tomatoes were unloaded by casual laborers but it was delayed for two days. At that time, some of the tomatoes were found to be bad. So, defendant decided to sell the tomatoes as they felt that tomatoes could not arrive in Covent Garden market in a good and saleable condition. When plaintiff found out about this, plaintiff wanted to claim damages from defendant. The court was held that plaintiff was entitled to damages because defendant ought to have communicated with the plaintiff when the ship arrived at Weymouth to get instruction. As defendant has failed to communicate with plaintiff when they could have done so, thus, there was no agency of necessity. |

|

|

Great Northern Railway Co. vs. Swaffield (1874) L |

plaintiff railway company had transported a horse to a station on behalf of defendant. When the horse arrived, there was nobody to collect it. So, the plaintiff sent it to a stable. A number of months later, the plaintiff paid the stabling charges and then straight to recover what it had paid from the defendant. In this case, the court was held that the plaintiff’s claim succeeded even though he is involved in the extension of doctrine of agency of necessity to include carriers of goods by land. There was an agency of necessity because the plaintiff was found to have had no choice but to arrange for the proper care of the horse. Great Northern Railway Co. vs. Swaffield (1874) LR 9 Exch 132, the plaintiff railway company had transported a horse to a station on behalf of defendant. When the horse arrived, there was nobody to collect it. So, the plaintiff sent it to a stable. A number of months later, the plaintiff paid the stabling charges and then straight to recover what it had paid from the defendant. In this case, the court was held that the plaintiff’s claim succeeded even though he is involved in the extension of doctrine of agency of necessity to include carriers of goods by land. There was an agency of necessity because the plaintiff was found to have had no choice but to arrange for the proper care of the horse. |

|

|

Prager v. Blatspiel, Stamp and Heacock Ltd [1924] 1 KB 566 |

which was regarding there must be a genuine necessity and the agent must act bona fide. After the outbreak of First World War, the plaintiff who was from Romania contracted to buy a number of furs from defendant who was from London. Plaintiff was intended to wait and ask defendant to deliver the furs which were largely paid until the war was over. At that time, Romania was occupied by the Germans and communication between both parties became impossible. The furs that were stored were increasing in value. Towards the end of the war, defendant began to sell the furs locally with assumption that occupation of German will be continued. When the war ended, the plaintiff demanded delivery from defendant but the defendant only told the plaintiff that the furs had been sold off under agency of necessity. The court held that there was no agency of necessity because the plaintiff was willing to wait for goods which were appreciating in value and it is clear that defendant acted against bona fide when defendant sold off the furs which got higher value at that time. |

|

|

Creation of agency by marriage and cohabitation |

A wife or de facto spouse is presumed to have authority to pledge the husband’s credit for necessaries in keeping with their social status. Necessaries are items such as food, clothing and medical attention for the spouse and the children in keeping with the family’s social standing. Necessaries for which a wife can pledge the husband’s credit as his agent do not include luxury items or items such as jewellery |

|

|

Pianta v Macrow and Sons Pty Ltd (1925) |

trader who sold a wife a diamond ring on credit cannot claim its cost from the husband if the wife does not pay for |

|

|

Harris v Morris (1801) 170 E |

If the husband has expressly informed traders not to supply any goods on credit to his wife, then it is unlikely that the husband will be liable for the debts incurred by the wife as his agent. |

|

|

Miss gray ltd v catheart |

A wife was supplied with clothes to the value of $215 on her husband's credit. The husband refused to pay for them. When sued by tradesman, the husband proved that he had paid his wife $960 a year as allowance. The court held that husband is not liable. |

|

|

Agency by Estoppel |

he term ‘estoppel’ is a legal term and means that a person who has let another person believe that a certain state of affairs exists, is not later permitted to deny that state of affairs if the other person has acted to his detriment in reliance of that state of affairs. He is estopped or prevented |

|

|

from taking a different position. Therefore, in the law of agency if a person by words or by conduct represents to the world that someone is his agent, he cannot later deny that agency if third parties had dealt with that person as if he was the agent. |

Example : If Piyal (the principal) has for several moths permitted Sunil to buy goods on credit from Prasad and has paid for the goods bought by Sunil, Piyal cannot later refuse to pay Prasad who had supplied goods on credit to Sunil in the belief that he was Piyal’s agent and was buying the goods on behalf of Piyal. Piyal is stopped from now asserting that Sunil is not his agent because on earlier occasions he permitted Prasad to believe that Sunil was his agent and Prasad had acted in that belief. |

|

|

Rama Corporation v Proved Tin and General Investments Ltd [1952] 2 QB 147, |

the English Court of Appeal emphasized three main requirements for agency by estoppel; i. A representation by a principal ii. A reliance by a third party on that representation iii. In A reliance by a third party on that representation An alteration of the third party’s position resulting from such representation. |

|

|

Lloyds Bank Ltd v Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China (1929) 1 KB 40, |

one Lawson , a senior employee of Lloyds Bank fraudulently drew cheques on the bank’s account and paid them into a person al account he maintained at the Chartered Bank. When Lloy Bank discovered the fraud, they claimed the value of the cheques so drawn from the Chartered Bank. The Chartered Bank argued that Lawson was an accredited agent of Lloyd’s Bank and therefore Lloyd’s Bank was liable as the principal for the agent’s acts were unauthorized. No ds even if they The Court refused to accept this argument by saying that the Chartered Bank should have questioned how a bank official was paying cheques of his emp loyer into a private account. estopel applied because the Chartered Ba nk could not prove that their loss was cause d by any representation of Lloyd’s Bank. Further it was the Chartered Bank’s own negligence that caused the loss. Therefore, Lloyd’s Bank wavs held not liable for the fraudulent act of Lawson |

|

|

Creation of agency by ratification. |

Ratification means that the principal adopts or confirms an earlier act done by the agent which was not binding on the principal. Ratification is treated as equivalent to original authority and by ratification the relationship of principal and agent is constituted retrospectively or retroactively. Example : Sunil who is Piyal’s agent has on 10 January 2009 purchases goods from Prasad on credit without Piyal’s permission. After the purchase, on 20 January 2009, Piyal tells Prasad that he will accept responsibility to pay for the purchases although at the time of purchase the agent had no authority to buy on credit. Piyal’s subsequent statement on 20 January 2009 amounts to a ratification of the agent’s (Sunil’s) purchase of goods on 10 January 2009. For agency by ratification to arise, some essential conditions must be satisfied |

|

|

Keighley Maxsted & Co. v Durant [1901] AC 240 |

The agent’s act that is ratified must have been done expressly on the principal’s behalf. The third party with whom the agent contracted must have been aware that the agent was acting not for himself but on behalf of the principal. If the agent had not earlier disclosed to the third aprty that he was acting for another, then that act cannot be later ratified by the principal. |

|

|

The ratification must be based on full knowledge of the material facts. The ratification must take place within a reasonable time. A forgery cannot be ratified |

. A ratification will not have the effect of making a forged signature a good and valid signature. This is because if you permit a forged signature to be made valid by ratification, you will in effect be condoning or accepting a criminal offence. |

|

|

Metropolitan Asylum Board v Kingham |

ratification took place after 10 days and this was held to be too long. Limelight have managed to ratify the act within 9 days, which has not passed the 10 days, therefore ratification is still in order. It is important to note that the reasonable will depend on the circumstances. |

|

|

Brook v Hook (1871) [18] |

it was stated that a principal could not ratify a forged signature on a cheque, as this was unlawful. |

|

|

Bird v. Browan, |

supra, the question really decided was that ratification could not cut off the intervening rights of third person |

|

|

Boston Deep sea Fishing Co v Farnham [1957] |

Facts An English agent operated a French trawler during a time when France was operated by the enemy Post-alienation, the French company purported to ratify the English agent’s conduct throughout the war Issue Was the ratification effective? Decision No Reasoning Aliens cannot ratify, and the French company was an alien at the time of the unauthorised tax English agents not liable for income ta |

|

|

Kelner v baxter |

A group of company promoters for a new hotel business entered into a contract, purportedly on behalf of the company which was not yet registered, to purchase wine. Once the company was registered, it ratified the contract. However, the wine was consumed before the money was paid, and the company unfortunately went into liquidation. The promoters, as agents, were sued on the contract. They argued that liability under the contract had passed, by ratification, to the company and that they were hence not personally liable. It was held, however, that as the company did not exist at the time of the agreement it would be wholly inoperative unless it was binding on the promoters personally and a stranger cannot by subsequent ratification relieve them from that responsibility. |

|

|

Grover & Grover V. Mathew [1910] 2 KB 401 |

Ratification on a policy of fire insurance was made after a fire had happened, the principal ratified the agent’s act after the premises had been destroyed by fire. Therefore the ratification was held to be ineffective, because the ratification on agent’s act should be done before the loss of goods. According to S153, CA 1950 |

|

|

Different types of Agents. Mercantile Agent |

A Mercantile agent is one who has authority either to sell goods or buy goods or to raise money on the security of goods. |

|

|

Factors |

A factor is a mercantile agent to whom goods are entrusted for sale. He enjoys wide discretionary powers in relation to the sale of goods. He can sell the goods in his own name upon such terms as he thinks fit. He may pledge the goods as well. |

|

|

Commission agent |

A commission agent is a mercantile agent who buys or sells goods for his principal on the best possible terms in his own name and who receives a commission |

|

|

Del Credere Agent |

This is an agent who in consideration of an extra commission, guarantees his principal that the third persons with whom he enters into contracts on behalf of the principal shall perform their financial obligations. Example : he assures the principal that if the buyer does not pay, that he, the agent, will pay. Therefore, he is a special type of agent who acts as a guarantor (surety) as well as an agent. |

|

|

Bowstead and Reynolds on Agency 19th para 3- 018 |

An agent has implied authority to do whatever is necessary for or ordinary incidental to the effective excusing of his actual express authority in the usual way |

|

|

Agent is impliedy authorised to carry out things |

incidental to carrying out his express instructions. |

|

|

ANZ Bank Ltd v Ateliers de Constructions Electriques de Charleroi (1966) 39 ALJR 414 |

Privy Council decided the agent could justifiably be taken by an outside such as the bank to have had implied authority from P to bank the cheques given the circumstances • A was their sole agent in Australia • There was a written agreement btw them • A had negotiated a contract with TP & the contract price was payable in Australia in AUS currency • Progress payments were made by chqs in favour of P c/- its agent which he indorsed into his own bank account • P had no bank account in Australia |

|

|

Where a person is appointed to a particular position and it is usual for that office to have contratual powers, |

the principal is implied to have conferred those powers as well. |

|

|

In Panorama Development (Guilford) Ltd v. Fidelis Furnishing Fabrics Ltd (1971) 3 ALL ER 16, |

a company secretary exceeded his actual authority in hiring motor vehicles from plaintiff. The court had to decide whether the defendant company couls be taken to have authorised the transaction. It was held that the defendant company was liable because in appointing a company secretary, the defendant company was representing that the secretary so appointed had authority to enter into thise transactions with which company secretaries were usually concerned. The hiring of motor vehicles was part of company administration. |

|

|

Hamer v sharp |

.. |

|

|

Hely-Hutchinson v Brayhead Ltd [1968] |

Facts Hely-Hutchinson (also known as Lord Suirdale) injected money into his own company, Perdio Electronics This injection was indemnified by a Mr Richards on behalf of Brayhead Mr Richards was serving as the managing director of Brayhead, but was only formally engaged as its chairman Brayhead subsequently purchased Perdio Electronics, but Perdio still went into liquidation Hely-Hutchinson csued on the basis of Mr Richards’ indemnity Issue Could Hely-Hutchinson recover, did Mr Richards have the authority to give the indemnity? Decision Yes, yes Reasoning Lord Denning: the judge (at first instance) was correct that in acting as managing director, Mr Richardson had apparent authority to give the indemnity, but he also had actual authority my virtue of the office he worked in By working in (and being treated as working in) the office of a managing director, actual authority as to all of the acts a managing director would normally do exists unless it is otherwise limited |

|

|

Howard v sheward 1866 |

A estate agent warranted to a purchaser that a house was structurally sound. Held: the vendor was bound by his agent's statement since it was normal practice (and therefore within the agent's implied authority) for an estate agent to give an assurance. |

|

|

croper v cook |

.. |

|

|

Howard v Sheward |

|

|

|

is clear that actual authority depends upon the agreement between the principal and the agent, whereas apparent authority depends upon the representation made by the principal to the third party. Hence, both types of authority are not dependant on each other. |

The above statement is more precisely construed by Lord Denning in his decision of Hely-Hutchinson case. He finds this case quite similar to Freeman and Lockyer case. In that case, the chairman was held to have implied actual authority whereas, in latter case, Mr Kapoor was held to have apparent authority. Lord Denning MR held in the Hely-Hutchinson case that, “Ostensible or apparent authority is the authority of an agent as it appears to others. It often coincides with actual authority”. He identified it in Hely-Hutchinson v Brayhead Ltd that, the chairman acting as an appointed managing director by the board had apparent authority as well as implied actual authority. This case demonstrated that the two types of authority often overlap thus creating confusion between the scope of actual authority and apparent authority. (Maclntyre, 2008) The statement made by Lord Diplock in Freeman Lockyer case seems to be doubtful, which is described by the Lord Denning in more better way. Lord Denning regards apparent authority as power of an agent as represented to others. He considered that both types of authority may correspond to each other and can even exist together |

|

|

The requirements for apparent authority were explained by Slade J in Rama Corporation Ltd v Proved Tin and General Investments Ltd[1952] 2 QB 147: |

The principal, or someone authorised by him, must have represented to the third party that the agent had authority to act on behalf of the principal. This representation, which may be of fact or law, may be made by words or conduct or may be implied by previous dealings between the parties or from the principal’s conduct. In Armagas Ltd v Mundogas SA [1986] AC 717, the House of Lords confirmed that the representation must come from the principal and not the agent. In this case, the necessary representation was satisfied when Sue notified her suppliers of Ian’s appointment. The third party must have relied on the representation. It appears that Sofa’s Ltd relied on this representation when agreeing to sell the sofas. The third party must have altered his position although not necessarily to his detriment. This third requirement appears nowadays to be satisfied simply by the third party entering into the contract itself (see, for example, the judgment of Diplock LJ in Freeman & Lockyer v Buckhurst Park Properties (Mangal) Ltd). |

|

|

(Lord Diplock in Freeman and Lockyer v Buckhurst Park Properties) |

Actual authority and apparent authority are quite independent of one another. Generally they coexist and coincide but either may exist without the other and their respective scope may be different.” |

|

|

Freeman and Lockyer v Buckhurst Park Properties [1964] |

Facts One director of a Buckhurst, its agent, commissioned Freeman and Lockyer as architects for their Buckhurst Park Estate project Buckhurst later refused to pay their invoices, saying that the director was not authorised to enter into the transaction which commissioned the architects Issue Was the company bound to pay Decision Yes Reasoning The director had acted as the managing director of Buckhurst There are two types of authority, actual and apparent authority The director did not have actual authority; the articles of association prohibited the director’s action, requiring all four directors to agree on such actions being taken There are four pre-conditions to apparent authority: a representation made by the principal (company) to the third party (architects); authority of the principal to make that representation; inducement of the third party by the representation into a contract and capacity of the principal to enter into that contract The representation was made by the appointment of the director into his position, whose office would normally provide powers of authorisation; the company had the power to appoint its own directors; the architects were induced into carrying out the work by the representation of the company that the director had authority and the company was not prohibited (by way of its articles of association) from entering into contracts such as that with the architects The director therefore had apparent authority and bound the company |

|

|

Summers v Salomon (1857) |

Facts The defendant principal owned a jewellery shop, which employed his nephew as agent After leaving the shop, the nephew ordered jewellery from suppliers After taking delivery of the jewellery, the nephew disappeared Issue Was the defendant liable for the acts of his nephew? Decision Yes Reasoning Although actual authority has been terminated, the defendant’s representation of his nephew’s authority was continuing, and therefore the nephews apparent authority still existed |

|

|

Summer v salmon |

|

|

|

Alteration of position |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Watteau v Fenwick (1893) ] |

Facts A pub owner named Humble appeared to own and manage a pub Humble in fact acted for an undisclosed principal, when he ordered cigarettes from the claimant, and failed to pay for them Humble was not authorised to purchase cigarettes by virtue of his actual authority Apparent authority and undisclosed principals are incompatible Issue Was the undisclosed principal liable to the cigarette vendor? Decision Yes Reasoning Purchasing cigarettes was within the range of acts usually carried out by a landlord, therefore the defendants were bound Opinion: this case undermines the doctrine of apparent authority, as there is no apparent possible source for the representation: at the time of the purchase of cigarettes, the principal did not exist and so obligations could not be conferred thereon; it is either plainly wrong, or there is an alternate justification for apparent authority which has not since been mentioned in litigation Tettenborn’s justification circumvents agency law altogether: [The agent] and the owner of the Victoria Hotel (whoever that might be) were one and the same person [and the same legal entity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

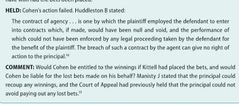

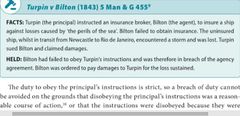

Turpin |

|

|

|

Bertram Armstrong & Co v Godfrey |

held liable for the loss. (1830) 12 English Rep 364 a broker was instructed to his principal to sell some shares when the market price reached a certain figure. The broker failed to do so. The market price then fell and he was forced to sell for less. The court held that the broke r, as agent, was liable to the principal for the loss he suffered, that is the difference in price |

|

|

Agent’s duty to exercise reasonable diligence, care and skill |

The standard of care that an agent must exercise in acting for his principal is that which is normally expected of a person engaged in such work. As long as the agent has acted with normal care and skill having regard to the nature of the transaction and has acted in a reasonable manner as would be expected from an agent employed in such undertaking, he will not be liable for negligence, even if his efforts were unsuccessful. |

|

|

Keppel v Wheeler (1927) 1 KB 577, |

an agent was employed by a principal to find buyers for a property. The agent found a buyer and the buyer’s offer was accepted by the principal (the seller of the property) subject to a sales contract to be drawn up. Subsequently, the agent received a higher offer for the property but neglected to inform the seller of the higher offer because the agent thought he had completed his j ob in getting the earlier offer. The court however, held that the agent should have informed his principal of the higher offer and because he had failed to do, he was liable to the principal (the seller) for the difference in the price of the higher offer. The agent had failed to exercise due diligence and care to get the maximum price possible for his principal. In deciding whether an agent has exercised due care and skill in performing his duties, the courts draw a distinction between (i) agents for reward (i.e. agentts who act for remuneration) and (ii) gratuitous agents (i.e. agents who are not paid for their services). It would appear that the absence of remuneration is a factor which tends to reduce the degree of care and skill that is expected of an agent. |

|

|

III. The agent must act in person and not delegate his duties |

The principal in appointing an agent expects him to act personally and not through others. Accordingly, unless when appointing the agent, the principal had permitted a delegation of duties, it is a well established rule of agency that an agent cannot delegate his duties to others. The Latin maxim is delegatus non potest delegare which means that a person to whom authority has been delegated may not delegate it to another. In other words, the principal is entitled to rely on and receive the benefit of the skill and knowledge of the agent he has appointed. |

|

|

McCann & Co v Pow (1975) 1 All ER 129, a |

principal appointed a firm of real estate agents to sell his flat. Without the principal’s approval, the real estate agents gave details of the flat to a sub agent who found a buyer. Then the agents asked for their commission for th court held that since they had delegated the sale to a sub e sale of the flat. The agent without the principal’s permission, the principal was not liable to pay the commission to the agent although the flat had been sold for the price requested. Page | 8 |

|

|

There are three main exceptions to this rule that an agent must not delegate his duties to another. These are; |

1. The agent may delegate his duties where there is an express or implied authority to delegate such as by professional or trade usage. ii. The Agent may delegate purely ministerial acts such as the signing of a letter or the giving of a notice where such act requires no personal skill or confidence. See Allam & Co Ltd v Europa Poster Services [1968] All ER 826 If the delegation is ratified or approved by the principal, then obviously it will be valid. In De Bussche v Alt (1878) 8 Ch. D, 286, the agent took the precaution of obtaining the approval of the principal for the appointment of a sub-agent. It was held that the delegation was valid and binding on the principal. Agents duty to act in the Principal’s interest The relationship of principal and agent is a confidential one. The agent must always act in the interests of and for the benefit of the principal. The agent’s interests must not conflict with the principal’s. If there is any problem for the agent to so conduct himself, he must relinquish his duties and terminate the agency. The courts have jealously upheld this duty very strictly and taken the view that the principal’s interest must always have priority over the agent’s. The agent must also disclose anything he knows or learns which may affect the principal’s interest and judgment. As the principal places trust and confidence in the agent, the agent must act honestly and must not do anything improper. |

|

|

McPherson v Watt (1877) 3 App Cas 254 the |

principals wanted to sell a property and were about to advertise its sale. Their solicitor told them that he would find a purchaser. The solicitor then got his brother to bid for the property and after the property was sold to him he got his brother to convey the property to the solicitor. When the principals discovered that the true purchaser was the solicitor their agent they applied to court and got the sale set aside. The agent had acted improperly. He had put his interests above those of his principal. The fiduciary or confidential obligation that is imposed on an agent requires that hi should not make a secret profit or commission in the performance of his duties. |

|

|

Reiger v Campbell Stuart (1939) 3 All ER 235 |

a principal wanted to buy a property and asked her agent to find a suitable property. The agent found a suitable property for £2000. Instead of informing the principal about this property for £2000, the agent got his brother to buy the property for £2000 and then pretended to buy the same property from the brother for £4500. He then offered the property to his principal for £5000 when its real value was £2000. Not knowing the truth, the principal bought the property for £5000 but subseq uently when the principal learnt the improper actions of the agent, she claimed a refund of the profit the agent had made and the court held in her favour and ordered the agent to pay the difference to the principal. Page | 9 Any financial advantage an agent receives in the performance of his duties, including a bribe, is considered to be a secret profit |

|

|

Bussche v Alt (1878) 8 Ch D 286, |

an agent who was asked to sell a ship bought is himself when he was unable to find a purchaser at the fixed pr ice. But later he sold it to a third party at a higher price. The court held that the agent had to account to the principal for this profit. Because an agent is under a duty to account to his principal for all monies received by him as agent, he must keep his personal accounts and finances separate from the agency accounts and finances. He must not mix his principal’s money with his personal money. For example, he must maintain separate bank accounts. |

|

|

V. Agent’s duty not to divulge confidential information To act in the principal’s interest, |

necessarily implies that the agent is also under a duty of confidentiality. Not only must the agent not tell others about the principal’s business and affairs but he must not make use of such information for his personal benefit or interests. This duty of confidentiality (also called a duty of secrecy) is a well-known rule between the banker and his customer. A bank is the agent for its customer’s account to others. |

|

|

VI. Agent’s duty to maintain accounts |

A fundamental rule of the law of agency is that the agent must maintain proper accounts relating to his work as an agent. He must also not improperly mix his principal’s funds with his personal fund and if he does dso the law will presume that the entire sum belongs to the principal |

|

|

Duties of the Principal towards the Agent |

There are three main duties that the principal owes to his agent and the agent can in turn exercise these rights against the principal. . The right to remuneration The right to an indemnity T he right to exercise a lien Even if the above three rights of an agent are not expressly specified in the document appointing the agent, they will be implied by the operation of law. In other words, unless any of these rights are expressly excluded by notice to the agent, a principal is bound by them. |

|

|

Agent’s right to remuneratio |

The amount of remuneration that an agent can claim will depend on the agreement appointing the agent. In may established commercial situations like solicitors, stockbrokers and real estate agents, the remuneration will depend on the fees and commissions charged in that particular profession or business. However, it is advisable that the agent should clarify the amount and terms of remuneration when accepting the agency. |

|

|

II. Agent’s right to indemnity |

While acting for the principal, the agent may incur certain liabilities or make payments on behalf of the principal. In such circumstances the agent will be entitled by common law principles to be indemnified against such liabilities or to recover any amounts so paid |

|

|

. III. Agent’s right to a Lien |

A lien is a legal right that a creditor has to retain the goods of a debtor as security for the performance of an obligation. A good example is a landlord of a rented property who has not been fully paid the rent by the tenant. The law recognizes the landlord’s (creditor’s) right to hold on to any furniture or other goods of the tenant (debtor) until the unpaid rent is paid. An agent can exercise a lien over the principal’s goods which are in the agent’s possession until the amount due to the agent is settled. |

|

|

Doctrine of the Undisclosed Principal |

Where the agent contracts with a third party on behalf of a principal but does not inform the third party that he is an agent, it may be possible for the principal to subsequently reveal his existence as the principal and enforce the contract. This rule is known as the doctrine of the undisclosed principal. Such a person is obviously not a party to the contract but he can yet sue and be sued in his own name (as principal) on a contract entered into on his behalf by his agent so long as the agent had acted within a |